I am passionated about AI and Robotics. Currently doing my Master's in AI at the Open University and building robots. Located in the Netherlands.

Master in AI at Open University

Building robots for the food industry that are more dexterious, safe to use by design and make use of foundational robotic models.

Premaster AI at Open University

Software engineer at Plantlab, working on computer-vision\deep learning in Python and C++. And working with .Net\C# and React\Typescript

Bachelor Mechatronics at Avans University of Applied Sciences, graduated by successfully developing a computer vision product at PlantLab. Using C++, TensorRT and Triton.

In July I went to my first conference: Robotics Science and Systems in Delft. The experience was inspiring and I met a lot of nice people. The conference began with a day of workshops, where I chose to participate in the GenAI workshop. It featured a range of fascinating discussions on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) and the use of robotic foundation models in manipulation, which captured my interest. The next three days included a lot of networking. I had very nice conversations with researchers and professionals from various universities and companies. These days were complemented by more detailed presentations that spanned a broad array of topics, from navigation to control systems. This immersive environment helped me realize that my interests align strongly with manipulation, robot design, foundation models, HRI, and imitation learning. Entering the conference, I wasn't sure what to expect, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed the experience. It was very enjoyable to be at the forefront of the state of the art and to explore the unresolved questions that need to be answered. Overall I think the robotics AI field is the most interesting space right now with a lot of promises but also still a lot that needs to be figured out and I am very excited to be part of this!

Building and designing robots require a few different disciplines, CAD

drawing, choosing the right transmission system (motor + gearing),

prototyping with for example 3D printing, electrical design, and

software integration. Luckily while studying Mechatronics I learned

quite a few of these things but applying them in the real world can

still be challenging at times. During prototyping for example, it is

essential to keep in mind the Design for manufacturability (DFM)

aspects, which limit producable shapes and materials. An easy way to

prototype without having the full picture of DFM is making use of 3D

printing, which is currently quite cheap and reliable. To come back to

building robots, a few key aspects are I think important when creating

robots that eventually do useful things in a safe way, utilizing AI.

First of all, it is important that robots are not very expensive. This

is needed because a lot of advances in AI and robotics, especially in

the manipulation area, focus on imitation learning. The data in

imitation learning is largely (besides simulation) coming from

teleoperated episodes. And thus it is a numbers game. More (good) data

is better models and cheaper robots mean more robots for a certain

price, which enables acquiring more data.

The second important aspect is ease of use when teleoperating the

robot. If the robot mimics the biology of a human arm in terms of

links and DOF then it is easier for humans to instruct the robot

through intuitive movement and by example. It also gives the

possibility to use internet data of humans moving which can more

easily be mapped to the robot's joints if they are similar to a human

arm.

The other aspects should be safety and reliability. Safety is

important if the robot works alongside humans. This usually is

achieved with torque sensors on output shafts or at the end effector.

My personal view is that robots that have less inertia together with

good current sensing of the motor can achieve safety, in a more

cost-effective way than robots with higher gears and dedicated torque

sensors. Reliability on the other hand is possibly harder to achieve

with a cheaper robot. I think here the important thing is choosing

reliable transmission without a lot of moving parts although this of

course is the opposite of what a robot does (it moves, and moves).

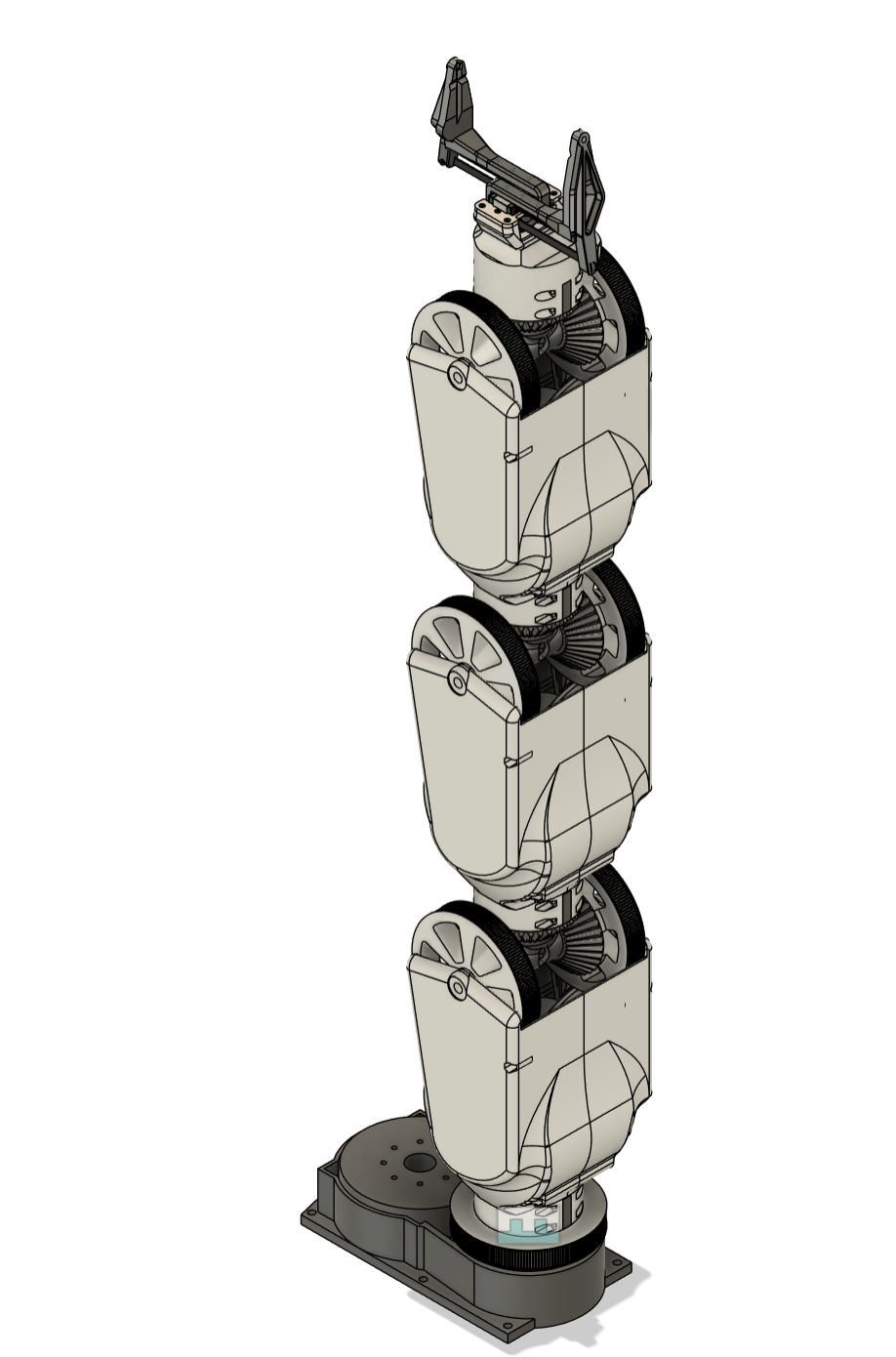

Furthermore, I built 2 robotic arm prototypes and here I want to share

a few of my lessons learned.

Blue like the sky

The first robot arm I build was based on the Berkeley Bleu robot arm [1]. This robot arm adheres to a few principles. It is relatively cheap, has 7 DOF just like a human arm, has relatively low inertia, and is easy to manufacture with a 3D printer. I modeled everything in CAD and began prototyping, taking hints about the design from videos and from the paper. After a few iterations prototyping, testing, choosing the right motor controller, more printing, etc. I was able to put everything together. Below is my version of the Blue robot arm.

During initial testing however and also once everything was together I quickly found out that the design, while it's good, is not optimal for my use case. The differential that is used is very handy, it combines the torque of two motors for 2 DOFs, however, the gears in the differential are not very precise when 3D printed. Additionally, the last DOFs in the arm are overpowered because each module (3 in total) is the same which helps in simplicity. But because they also use the same motors the torque in the last DOFs are over-engineered and are too large for what is needed, besides the increased weight that this brings is not advantageous. Both these problems are solvable (larger 3D printed gears or metal gears, and smaller motors in the last DOFs), and with some more thought and adaptation can this design be transformed into a very capable robot. I however moved towards another type of robot to learn what tendons can possibly bring. I still want to give credit to the designers of the Blue robot because it is very nicely thought out and generates some interesting points and thoughts on cheap and simple robot design for embodied AI.

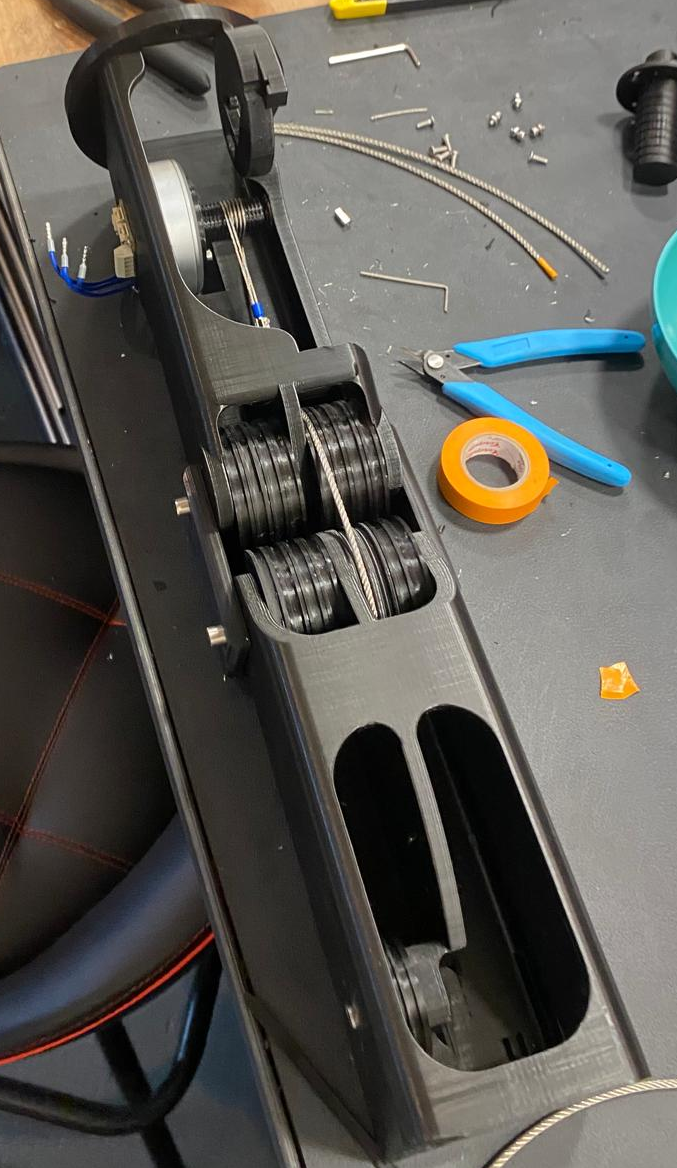

Tendon-driven robots glide and sway, with cable and tension leading the way.

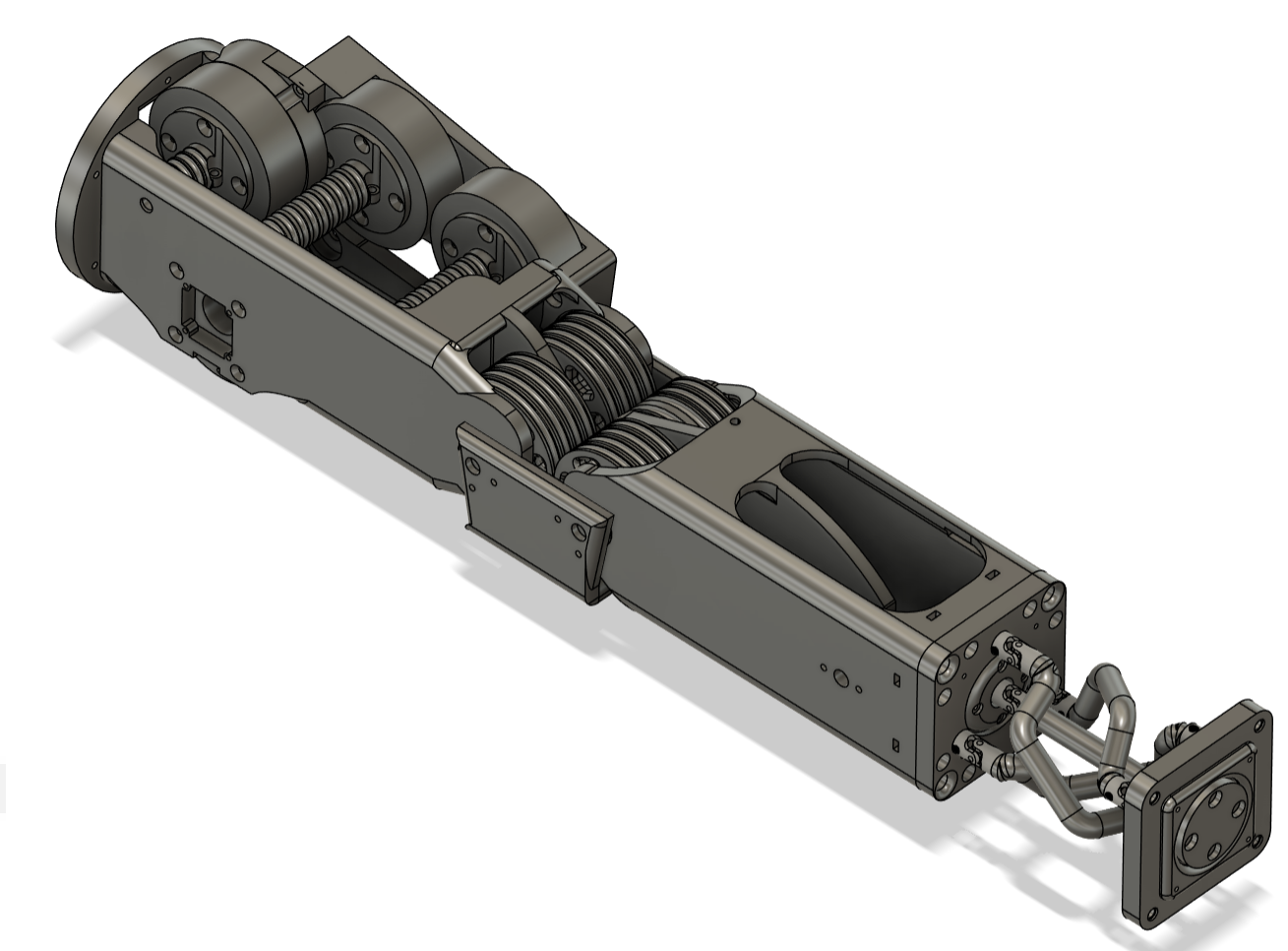

The next exploration in robot design was led by the design of the dynamic and low inertia robot LIMS I found from IRIM LAB KOREATECH. This lightweight tendon-driven robot arm is inspiring to watch on Youtube and its safety by design feature, because of these tendons is inspiring. However, the first and second iterations look quite hard to manufacture and assemble as seen in the LIMS1 paper [2] and videos on YouTube. The third iteration (YouTube link) however looks simpler in both its design and possibly in its manufacturing. This design features tendons in each of its joints which is I think somewhat overkill because the shoulder joints don't reap the benefits such as the arm joints do, which make use of tendons routed towards the upper arm to bring the weight of the motors more towards the base. Aside from this design decision, I think the usage of tendons in the elbow and for the lower arm and wrist are very cleverly thought out. Thus I went on to try to create a similar design to learn more about tendons and to find out how hard they actually are to work with. The LIMS design makes use of a virtual rolling contact joint for the wrist, which in the last version only consists of two bar linkage mechanisms, aside from the actuation bar. The other versions use three linkages and this was also the type I implemented (see image below). This mechanism is quite elegant, although not very stiff without strong tendons. I found out that using universal joints together with 3D printing can deliver quite an easy-to-make and simple virtual rolling contact joint, compared to a joint that uses bearing and axis for this connection. Furthermore, to enable motor placement in the upper arm, the tendons are wired through the elbow via a mechanism that keeps the tendons the same length when the elbow moves. This is cleverly designed but requires quite a few pulleys (4 for each DOF) which makes 16 pulleys in total (2 stationary). The tendons are connected via a winding pulley to the motors which is a very easy way to create a transmission that is quite high and has low backlash and friction. This is very beneficial, but the pain point is in the tensioning of the tendons. This is harder to do but if managed I think tendons-driven robotics can for a lower payload offer great characteristics. In my design, I however didn’t have enough time to make them work reliably but with enough iterations, I still think they can be a great way to create a transmission especially when you want to create low-cost and possibly 3D printed robots.

So to conclude I learned a great deal about hardware design, trade-offs, and design for manufacturability. The more opinionated look on robot hardware that I developed, helps me in creating new robotic hardware for use in research and application of embodied AI.

[1] D. V. Gealy, S. McKinley, B. Yi, P. Wu, P. R. Downey, G. Balke, A. Zhao, M. Guo, R. Thomasson, A. Sinclair, P. Cuellar, Z. McCarthy, and P. Abbeel, "Quasi-Direct Drive for Low-Cost Compliant Robotic Manipulation," arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.03815, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.03815

[2] Y.-J. Kim, "Design of low inertia manipulator with high stiffness and strength using tension amplifying mechanisms," 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2015, pp. 5850-5856. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15512797